Mediations #32: Why don't you get the compensation increase you think you deserve?

The context you might be missing can lead to a wrong perception.

As an engineering manager, I have various conversations and make decisions about compensation changes after promotions and annual reviews. People are sometimes satisfied with decisions; sometimes not. Discontent is higher when they believe they have exceeded expectations but have not received sufficient reward. Then, we have a long conversation about the why.

In these conversations, I explain how these decisions are made, not to manipulate their thinking. Instead, provide them with context so they can evaluate their satisfaction and next steps, enabling a better conversation. I have observed that this approach helps people (even when they are happy with the compensation change). They judge the change more effectively and make a better-informed decision about whether to seek higher pay elsewhere or stay.

I’m sharing below the same context I bring into these discussions. After I learned this context and mindset, it helped me form my own perception and set better expectations for my own compensation, too.

Often, unhappiness stems from misjudging the company’s situation, especially when leaders’ messages in company-wide communications are misleading. Sometimes, executive leaders want to celebrate small wins to motivate people, creating a “financially great” perspective, even when the reality is being in financial distress. Because most employees don’t share the same context as executives, they view the evaluation differently.

In the last two Mediations issues (1 and 2), I talked about psychology and economics and their contribution to efficiency and effectiveness. Understanding the company’s situation is another area where we need lenses from economics and psychology, combined with finance and accounting.

What contributes to decisions for compensation?

Behind the closed doors, multiple factors contribute to the budget evaluations and decisions. Not in any particular order:

The company’s current financial performance (+/- profit, revenue, etc.)

Investment plans

Growth (part of CapEx)

Deals with (new and existing) shareholders

Savings for the future

Strategic Investments (Merge&Acquisitions, Research, etc.)

Inventory & Logistics (might not apply to all)

Tax and Debt

Operational Expenses (OpEx)

Market conditions

Product Market (competition, expansion, etc.)

Economic Outlook (world and country)

Talent Market (finding the needed talent)

Risk tolerance and appetite

Company goals

and probably a few other things that I am unaware of

Within all these factors, the executive leadership team tries to figure out where to invest (or cut) the money so the organization can achieve its goals. The goals can range from finding product-market fit to selling the company, from an IPO to paying off debt or fines.

For example, the company can scale up its Operational Expenses (OpEx) if it plans to support growth through hiring or faces intense competition for the product or has a competitive talent market.

Leadership can also reduce OpEx if debt levels are high or if growth or financial performance doesn’t support the expenditure.

The company might have a large inventory it needs to reduce, and therefore can temporarily scale back production to lower output (though this is rare for software companies).

There are possible variations and combinations of all these factors. Once executive leadership decides, the budget is allocated to departments and teams.

The budget of departments

These contributing factors cascade across all departments, though some elements are eliminated along the way (e.g., shareholder deals, debt, taxes, and more).

For example, if the company has two departments, the decision to split operational expenses (the category that determines compensation) between them may depend on growth, strategic investments, product and talent market conditions.

A very profitable company can keep a department’s budget at last year’s level or shrink it, eliminating any potential compensation increases for the people working in that department. Unless the department can manage the budget differently or secure additional funds, there might be no money available for any compensation increase. In these situations, a layoff is even being considered (remember, even when the company is profitable).

From departments, the contributing factors cascade down further to the teams. A department’s leadership team does a similar exercise to decide where to invest its available budget. They may take risks to create a competitive edge for the entire organization by forming a new team. They may also cut another team’s budget to support this. They may invest heavily in CapEx and don’t add any additional funds to OpEx, halting any compensation increases.

Once a department’s budget allocation is complete, the conversation and decisions shift to OpEx: compensation for teams and individuals.

Team and individual performance, at last

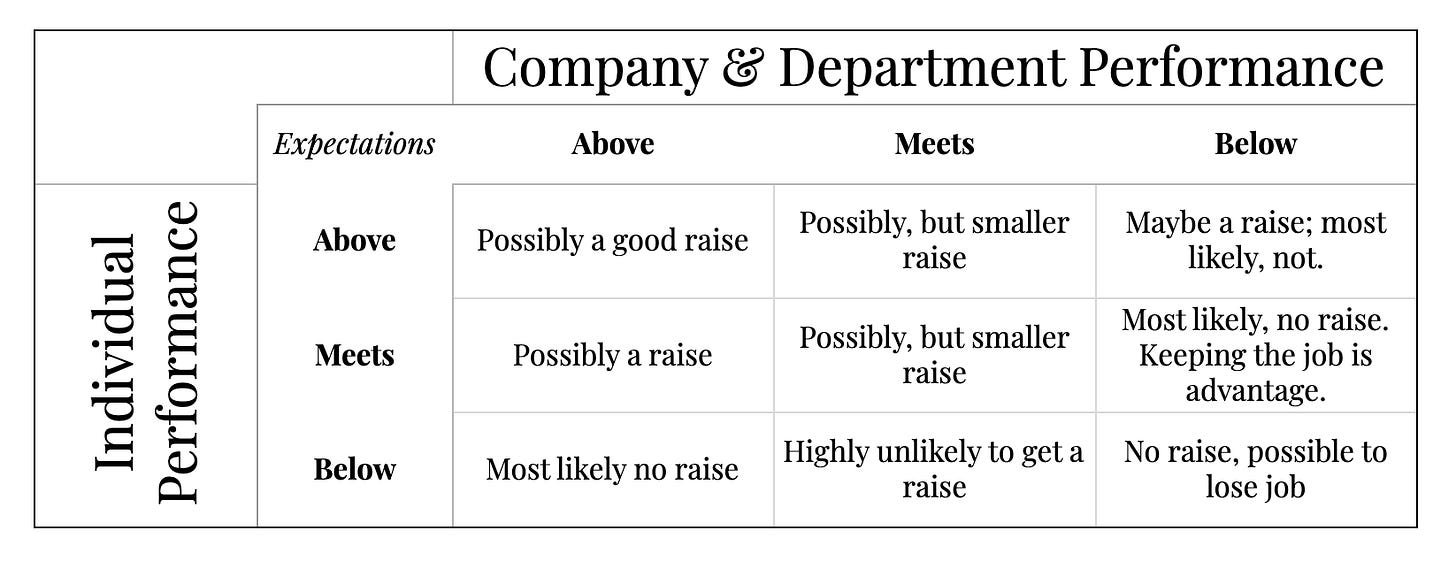

In my conversations, I often explain the compensation decisions using a matrix after the company and department context.

I simplify all of the above to better focus on and assess the impact of individual performance on compensation. I consolidate all of the contributing factors under “company and department performance.” Think of this as the sum of the parts. This is one side of a matrix.

On the other side of the matrix, we have individual performance. Most often, an expectation framework (sometimes defined by career matrices) is used to evaluate an individual’s performance.

For both sides, I use the following: meets, exceeds, and above expectations. Compensation changes or staffing decisions can be made based on a combination of these two factors.

Here is an example matrix:

Needless to say, there is never a guarantee of a compensation increase even when both company and individual performance is above expectations. A company can be profitable for a long time but can decide to invest these profits fully into CapEx or R&D. It can also decide to shut down one department/team to focus on other areas.

On the other hand, even when an individual’s performance falls below expectations, the leadership can still decide to increase their compensation. That was normalized in the zero-interest-rate policy (ZIRP) era, especially while the talent market was hot. Many people who started working in that period mistakenly consider it “the normal way” compensation works.

Although I didn’t mention an individual performance evaluation much, that aspect of the matrix above is another dimension of these decisions. That part of the matrix is often discussed deeply. Although more comprehensive knowledge exists for individual performance management, many managers (including me) make mistakes because of misalignment on expectations.

Performance evaluations are based on (ideally) aligned expectations. But a perfect world, sadly, doesn’t exist and aligning expectations is hard. On top of it, biases (e.g., gender bias, unconscious bias) still impact these decisions. Also, tons of reasons may cause conflicts between manager and individual, ending up with the decision at the wrong cell of the table above.

Another aspect is that a manager can distribute the budget within a team while keeping everyone’s compensation balanced to prevent unfairness. Sometimes, a team as a whole can work remarkably well while one individual can shine above them. But when the compensation review comes, the change might feel small compared to others’ to keep everyone’s compensation balanced.

All things should come together

There are many more details on how these decisions are made, but this should provide a good enough overview.

Seeing all the contributing factors AND understanding them takes time and energy. However, I found that once an individual understands the context, their judgment of the situation improves. What matters is understanding the contributing factors and forming more accurate expectations of the compensation.

Ultimately, working with a company is a business contract. An individual offers skills in exchange for money. If the skills (as a whole) are valued for the organization (and the more irreplaceable they are), the more leverage they’ll have. Combined with a deeper understanding of the factors above, they can form a clearer perception.

“Both happiness and unhappiness depend on perception.” — Marcus Aurelius

Good to Great

I share max three things I found interesting, sorted by good to great.

Good: As you might know that I love solving real problems. Reading three ways to solve problems gave me a good framework.

Better: I always enjoyed Gurwinder’s writing. As much as I don’t read most predictions (as they are like fortuneteller’s story), I found Gurwinder’s 26 Useful Concepts for 2026 post as a better approach. Short and crisp.

Great: The Size of Life. Just go and see yourself (ideally on a computer). You won’t regret.

Recently, I wrote about

The Unbearable Joy of Sitting Alone in A Café: Currently, I am in the last week of PTO from work. I wrote this two weeks ago while I was trying to slow down the time as much as I could. It resulted in this post. A lot of observations, some reflections. (Also, it made it to HN’s front page. I rarely read comments there. But if you want to join the conversation, it’s here.)

I added bunch of new ideas as notes to my Zettelkasten. All notes are atomic.

A small journal entry: Easy is the enemy of good.

Until next time,

Candost

P.S. I reorganized my blog’s front page and simplified a lot of things with a goal to make discovery easier. Let me know how you find it!